Separated by 28 years, Beijing and Lillehammer are about as different of Winter Olympic hosts as any that have held the Games.

Back in 1994, Lillehammer was the site of the last men’s Olympic hockey competition before NHL players redefined it and there were a handful of local players and officials that took part.

In the end, Sweden beat Canada in a shootout to win gold, the decisive goal scored by future Hall of Famer Peter Forsberg using a move that was later immortalized on a postage stamp.

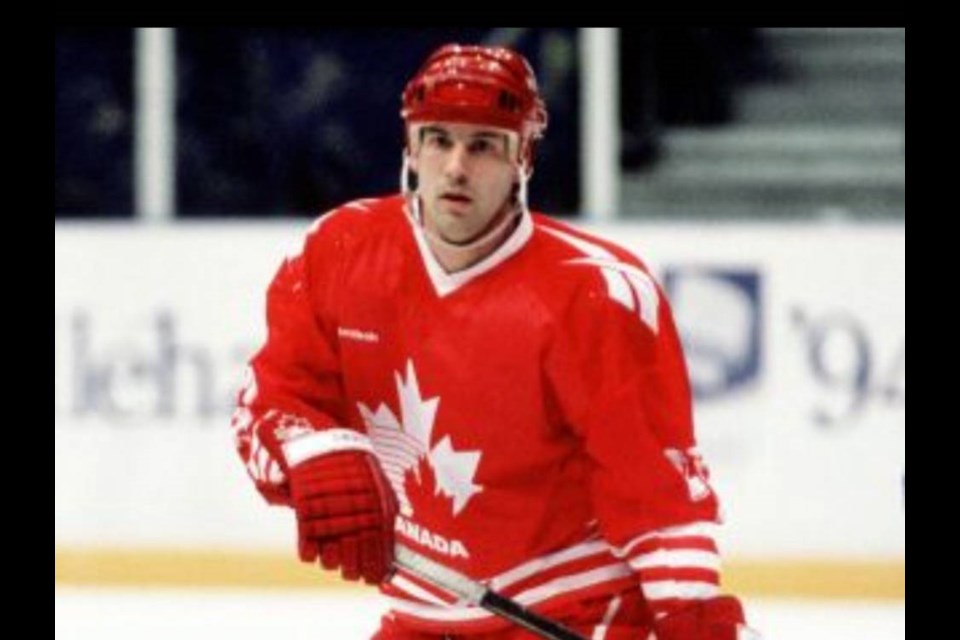

By 1994, Chris Kontos was a veteran pro. He had played 230 NHL games, 20 more in the playoffs, and was coming off his best season as a pro with the expansion Tampa Bay Lightning. But a contract dispute followed, which allowed Kontos to pursue the Olympics again, two years after he had been a late cut before the 1992 Games in Albertville, France.

“I had always wanted to play in the Olympics,” says Kontos, pointing out that as someone with Greek heritage he was keenly aware of its cultural impact. “I was there in (1992), but had been a bit banged up when they added (NHLers) Dave Tippett and Dave Hannan, I got bumped. Now, I had the contract thing with the Lightning and (jumped) at the opportunity.”

That opportunity was presented to Kontos from a fellow Penetanguishene resident, Paul Henry.

Henry had been put in charge of assembling the team after Albertville. Though the job title was different, Henry was effectively Team Canada’s GM. Henry had already been heavily involved in the game at the top level, including a four-season run with the New York Rangers as a sports psychologist and player development coach.

“It’s still the best thing, the highlight of my six decades in hockey,” remembers Henry, “It’s not close, even better than being involved with teams that had made it to the Stanley Cup final.”

Beyond Kontos and Henry, Alliston native Manny Legace was Canada’s backup goalie. Two Barrie residents, defenceman Bill Stewart, the future Colts coach, and goaltender Mike Rosati, played for Italy, where both were playing at the time.

Kontos scored twice in Canada's 7-2 victory in a preliminary round game played between the two countries. Italy eventually finished ninth, which remains that country’s high-water mark in international hockey.

Almost three decades later, the Olympics has effectively returned to its former self. It’s an imperfect comparison because there are clear differences now as well – Henry had the luxury of assembling a team over two seasons, for example – but, like 1994, NHL players are not taking part when action starts on Wednesday.

NHLers or not, 1994 was a classic tournament and the gold-medal game was every bit as epic as the overtime victory Canada earned 16 years later in Vancouver, with NHLers taking part.

In 1994, the International Olympic Committee had previously moved the Winter Games up two years, so it no longer conflicted with the much larger Summer Games. The quick turnaround allowed for a particularly gifted cohort of players to take advantage of the much narrower window before embarking on a pro career.

On Canada alone, more than half the roster would go on to NHL careers, highlighted by another future Hall of Famer Paul Kariya. Czech-born Petr Nedved, after qualifying as a Canadian citizen while playing for the Vancouver Canucks, was also in a contract dispute.

“That was our top line,” Henry recalls of the Kontos-Nedved-Kariya forward unit. “And they were great for us.”

Both Kontos and Henry’s voice brims with pride at the experience, even if the disappointment still lingers from not winning gold — or rather losing it in such a fashion. Canada had led until Sweden tied it on the power-play in the waning moments. Overtime solved nothing and extended the game to a shootout, the first and only time that the gold medal had been decided that way.

“At the time when I got the silver medal, I wanted to throw it in the garbage,” remembers Kontos, who assisted on Kariya’s goal in regulation time. “You win gold but lose (to get) silver, right?

"But now when I think of it, we came in ranked eighth, it was pretty incredible.”

Henry says he had a special feeling about the group.

“I think when we beat the U.S. at Maple Leaf Gardens about a month before, I knew that we could (potentially win gold).”

Does Henry ever think of what could have been?

“I last saw Forsberg a few years ago,” explains Henry. “He told me that I need to let it go. I might be able to (some day).

“It’s still the most intense game I’ve every seen or been a part of in the final 10 or 12 minutes, especially in the last eight or so, when Sweden really started coming after us.”

Kontos is more circumspect, but no less regretful especially since he didn’t get a chance to go in the shootout.

“I was kind of waiting for the tap on the shoulder,” he remembers. “I was a goal scorer and wanted a chance.”

Henry, who had a parallel career as a psychologist in Canadian prisons and mental hospitals, is now retired from that job. He remains active in hockey, working primarily to help a few Canadian major junior teams find import players. Henry often kibitzes at the Sadlon Centre, full of stories that would leave any hockey fan rapt for hours, including a few Lillehammer yarns.

“I snuck (St Louis Blues executive) Ron Caron into the Athletes Village so he could sign Peter Stastny,” he says. “And of all the people I saw and (assessed) working in maximum-security institutions, none left me more cold than Tonya Harding, I stood two feet away from her in Lillehammer.”

Kontos and Henry (and Legace) await a rescheduled team reunion, a get-together in Collingwood had to be delayed because of the pandemic.

After dabbling in media, Kontos recently sold his marketing company. He is now involved with a product called Raptor Liner, a more durable bedliner than traditional automobile paint.

After a five-year OHL career and four more at St. Francis Xavier University in Nova Scotia, Kontos’ son Kristoff is playing pro hockey in, of all places, Sweden. Kontos and wife, Joanne, also have a daughter, Joelle, who is an opera singer.

“(Kristoff) sometimes gets ribbed by his teammates,” explains Kontos. “They try the Forsberg move in shootouts after practice.”

If they only experienced the real thing – it could be made into an opera.