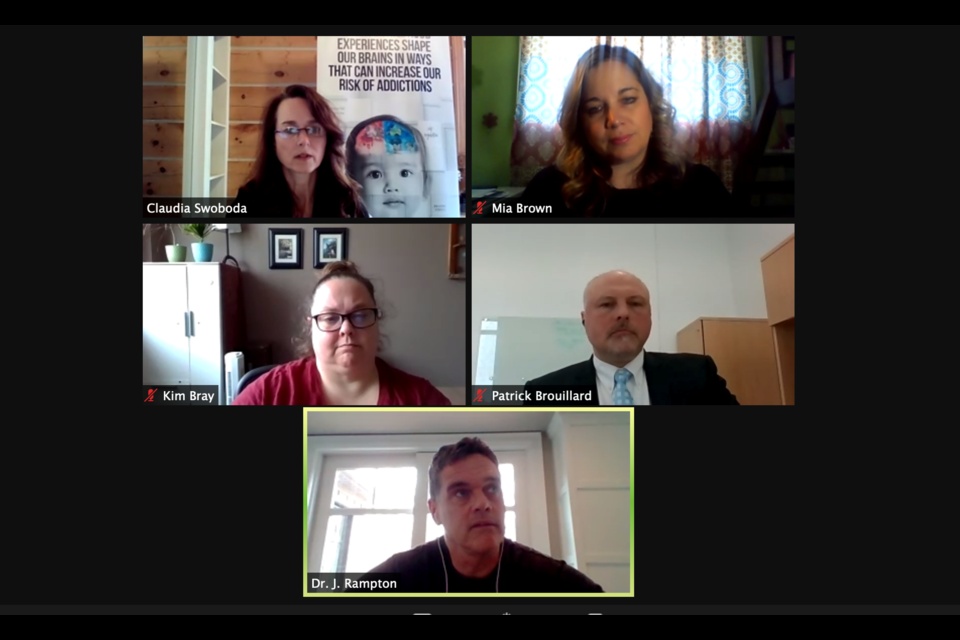

More than 300 people logged on to their computers Wednesday afternoon for an educational forum to learn more about opioids and how they are impacting the Barrie community.

Hosted in partnership with the City of Barrie, the Simcoe Muskoka District Health Unit and the Simcoe Muskoka Opioid Strategy (SMOS), the webinar featured speakers from a variety of sectors.

Opioids are typically produced to treat pain, however because of the feelings of euphoria that can come along with them, have the potential to become a problem. Most of the harm currently being experienced, explained moderator Claudia Swaboda, a public health nurse with health unit, is due to the synthetic opioid fentanyl.

“The presence of fentanyl in other substances dramatically increases the risk of overdose. It’s an extremely potent and deadly drug that can cause fatality even in trace amounts,” she said. “When we are speaking about the opioid overdose crisis — or poisoning crisis — what we’re really addressing is not so much the fentanyl people are being prescribed… but the problematic overdoses that we are seeing in our community is primarily in relation to the fentanyl that’s in the drugs we’re finding on the street.

"It’s a more lethal, potent and deadly mix of drugs that are currently out there.”

Worsening situation

Despite the additional attention being focused on the issue, the crisis is only getting worse, with Barrie reporting the third highest crude rate of emergency room visits for opioid overdoses in the province. From January to September 2020, the city saw 94 deaths, which she noted was 50 per cent higher than the previous three years.

“These statistics, these are people’s lives, but they do show a story," Swaboda said.

COVID-19 has presented additional challenges to an already difficult situation.

“Social isolation is a factor in harmful substance use, including that of opioids," Swaboda added. "With COVID-19, we’ve had an increase in social isolation so you’ve had an increased negative impact on mental health and addictions.”

Decreased availability of mental health and addiction services early on in the pandemic was a challenge, and continues to be a challenge. While an even more toxic drug supply on the street was an issue pre-pandemic, Swaboda said it’s gone off the charts in the last year.

“That is something we are seeing in Ontario, in our region and in Barrie," she said.

Dr. Joey Rampton, an emergency medicine physician at Royal Victoria Regional Health Centre (RVH) and Addiction Medicine at the Canadian Addiction Treatment Centre and Pain Clinic, deals with the opioid crisis daily while working in the emergency department at RVH.

“In the 20 years I’ve worked, us emerg docs would see maybe one overdose a year (each). Starting in July 2016, when powdered fentanyl became available, we don’t get through a single shift without each of us seeing at least one (overdose). It’s non-stop in Barrie. The expectation at that hospital is you’re going to see that when it comes in now," Rampton said.

At the addiction clinic, he said they have just under 1,000 patients and maybe five per cent or less are what he would consider to be homeless individuals.

“We’ve had doctors, dentists, counsellors, major business people, nurses… you name it and I’ve taken care of them," Rampton said.

Users playing a losing game

The introduction of fentanyl to street drugs, he said, has created a problem bigger than they’ve ever seen before.

“It’s not coming from the cartels. It’s the dealers, the last guys that are cutting it. It takes your $1,000 and makes it $2,000. Right now, there’s purple heroin, blue heroin and orange heroin on the street. If someone overdoses on that drug, I will guarantee you that the dealer will be sold out by the end of that day," Rampton said.

"You’d think they would avoid it, but understanding the addiction and the high people want to get, people are playing Russian roulette with a loaded pistol and there is no bullet missing. It’s just a matter of time," he added.

Over the course of the pandemic, Rampton said the numbers of individuals coming to the clinic to seek help dropped because so many were afraid to go somewhere and be around other people when so much was unknown about COVID.

“People didn’t want to go out. It’s gotten better, and we have it set up so it’s only one patient at a time, but the issue is there are a lot of people in the community that are not addicts that are drug users. We check all the urine in our patients and I can tell you about 15 per cent of marijuana in our community is cut with fentanyl. If your kid is smoking that and they have no tolerance, there’s a high risk of overdose," he said.

The issue is the community is not heroin, but rather 100 per cent caused by fentanyl.

“Cocaine right now, what we see in our clinic, is 60 to 70 per cent of the cocaine is cut with fentanyl," Rampton said. "There are people who do cocaine once in a blue moon, but the problem right now is any recreational drug use is very dangerous.”

When someone overdoses, they may get stereotyped as being an addict, but that’s not always the case.

“It could be any of us. It could be one of our kids," he said.

Help is out there

The Canadian Mental Health Association (CMHA) continues to offer the outpatient counselling, make referrals to residential treatment and local agencies, noted Kim Bray, team lead with CMHA addictions services. They are also offering education not only to clients about overdose risks, medication interactions, harm reduction and safety planning but also do community education about substance use.

“We are active in the community with the Simcoe Muskoka Opioid Strategy, which involves actively pursuing the supervised consumption site. We have identified very clearly there’s a piece of the continuum of addiction services that’s just not being met so we’ve been working over the last couple of years in making that a new addition to the continuum. It’s not the answer but it’s an addition to the options that will be available," Bray said.

Accessing help in Barrie, she added, is currently being done through their phone lines, where staff are trained to help a person get set up for intake. Despite their best efforts, there are occasionally wait lists for treatment.

“Over COVID, we actually have had very few waiting lists. Sadly, that means more folks are out there continuing to use instead of looking at making some changes, but for those who are looking for help right away, we’ve been able to help with that," Bray said.

Looking at the long term

A key focus for the health unit’s substance use and injury prevention program, pointed out Mia Brown, the program's acting manager, is harm reduction, which she said is a pragmatic approach to addressing drug use and meeting people where they’re at with their use.

“The programs, policies and systems are in place to reduce the harms that come from a social and health perspective when people are using substances,” she said.

There are several activities that are being conducted in the region and in Barrie, Brown added. One of the short-term strategies is ensuring access to naloxone for community partners such as police, the city, etc. Another activity is promoting harm reduction messaging through partnerships and encouraging the “buddy system."

“We know with many of the public health measures with COVID, people may be using alone or have decreased access to the typical services," she said.

Addressing the toxic supply of drugs in the community is another strategy, by providing prescription grade alternatives, such as hydromorphone and diacetylmorphine, for people who are using.

“It’s a little different than the methadone and suboxone treatment model, but it’s a way of providing a safe, uncontaminated supply to someone who is using," Brown said.

The new drug on the block

From a police perspective, the availability of fentanyl and opioids on the street is one of the biggest issues they face in their fight, noted Barrie police Det. Sgt. Patrick Brouillard.

“We are depending on these people who are mixing these who are untrained and don’t have education, so the end user doesn’t know what they’re getting and how many times it’s been adulterated on the way down the chain,” he said. “Recently, we’ve gotten information from street-level users about a substance they refer to as ‘grey death’. It’s being called that because it’s hyper potent.

"To most people who aren’t users, that would be a good reason to stay away. It’s concerning.”

While health unit officials are touting Wednesday's event as successful, they note it is only one piece of a multi-strategy approach to mitigate the harms of opioid use in the community, something that will require regular ongoing efforts that are sustained, resourced, co-ordinated and involve collaboration and commitment from every level of government and our community.

"We have received a lot of positive feedback around the event, including the need for future educational events and ongoing dialogue," said Kara Thomson-Ryczko, public health promoter with the health unit. "We continue to work with our community in further addressing the issue and impact that opioids has had within our community including the impact during the pandemic.

"We need to keep the conversation and the supports moving forward," she added.

A followup webinar is scheduled for Wednesday, March 24.