ADJALA-TOSORONTIO TWP. — While thousands of commuters pass through the intersection of Highways 9 and 50 every day in southern Simcoe County, few realize that on top of the hill on the northwest corner of the crossroads was once a thriving little town with a colourful cast of wild-west type characters and a rather dark history if you look deep enough past the written archives.

It was called Ballycroy – named after the hometown in Ireland of the original settlers who found it a good place to start a mill in the 1820s.

After a good run of around 55 years, the town was, for the most part, abandoned.

The main street is now overgrown and mature trees stand where businesses one thrived. If you know where to look, you can find remnants of where some of the buildings once stood, but for the most part Ballycroy only exists as a footnote in Ontario history.

The only original building still standing and occupied is the general store and post office, along with a barn on the property.

It was a thriving business in its day with a second-floor meeting and dance hall, and a main house that also served as a hotel.

Business prospered and, as more people moved into the town, it became a bustling little community.

By 1870, there was two churches, two general stores, a mill and complementary businesses, a millinery shop, a post office, a doctor's office, a veterinarian, and a blacksmith. It had all the trades and skills you needed to keep a town running.

There was also a small race track and a fairgrounds, but most notably there were four hotels and a liquor store – a lot of alcohol for a town of 200 people.

The thing about Ballycroy that stirred up resentment among its residents was that most, if not all, of its residents were Irish. That in itself was typical of early 18th-century immigrants to Ontario, but when you have a town that is filled with Irish of the Catholic faith and throw in a bunch of the Protestant faith, well in those days it could spell trouble. And it did.

The fact that the Protestant side decided to build an Orange Lodge in the middle of town did little to heal any local bad feelings that might have already brewed among the local populace.

The Fehely Hotel was one of the more notorious establishments in town. It was more of a flophouse than hotel, as it contained a second-floor single room where imbibers could sleep off the effects of a night of drinking rather than try to stagger their way home on a freezing winter night.

The current landowner had to tear the old place down several years ago when it just got to the point of being beyond repair.

“It wasn’t much of a hotel,” he said. “It was a saloon.”

You could see the years of wear on the floor boards of the hotel except for one long stretch at the end of the room that still had the original finish – and that was were the bar had been.

On nights when the Orange Lodge held its meetings, members would make the trek as a group for security reasons.

The Fehely patrons would keep an eye out for any stragglers and if you were unlucky enough to be caught alone on the street and of the wrong religious affiliation, you’d better be prepared to use your fists.

There were several legendary brawls on the streets of Ballycroy, no doubt fuelled by the hooch served in the hotels.

The other main hotel in town was the Small Hotel, owned by proprietor Peter Small. It was more of an upscale establishment known for its fine dining and liquor, and the famous ‘January Ball’ that attracted people from as far away as Toronto for a mid-winter soiree.

Mr. Small also operated the racetrack that featured betting and horse trading.

But tragedy struck on April 29, 1875, when the Small Hotel caught fire and burned to the ground along with a couple of nearby out-buildings.

Mr. Small and his family escaped the flames, but three young women who worked as milliners in the hotel perished in the flames and are buried in the cemetery at St. James Roman Catholic Church in Colgan. The grave marker easily located behind the church.

You would think one fire is bad luck, but two fires within a couple of months might make you more than a little nervous when you blew out the candles and went to bed.

When the hotel was destroyed, Mr. Small and his family moved to another building on the property.

That building also went up in flames two months later with the family again making a narrow escape.

The family remained in Ballycroy until 1879, when Peter finally decided it was best to leave town while they were all still healthy.

They moved to Toronto where Small operated another hotel before becoming a Divisional Court bailiff later on.

A third fire in 1878 at the Beamish hotel was no accident as it was discovered that it was set with some kind of incendiary device.

Although the blaze was extinguished before it could cause major damage, owner Richard Beamish figured it would be best to sell and get out of town before an arsonist had a second chance.

When fire destroyed Ballycroy’s Small Hotel and several other buildings in April 1875, it also destroyed much of the heart of the small but bustling frontier town.

The cause of the fire was never determined, but arson was considered, especially given that local entrepreneurs were known to be protective of their competing businesses.

When it was discovered that Peter Small held $21,000 in mortgages on the hotel – a huge sum of money at the time – the rumour mill went into overtime.

Mr. Small finally decided to leave town two years later, never to return.

Local stories still pass on the tragedy of the three girls who perished in the hotel fire. They were milliners – hat makers – who lived on top of Peter Small’s hotel.

Except that they were hardly girls.

Mary Fanning was 32 years old, Bridget Burke 28, and Margaret Daly the youngest at 24.

You have to read between the lines of this story for a more historical take on this tale.

In the 1870s, most pioneer women were already married and had children by age 20. Mary, at 32, would have been considered an old spinster in her time.

Why a town of only 200 people required three hat makers, all living above a hotel, leaves open a few other questions — but those answers are lost in time.

Not everyone in Ballycroy had a rough and tumble time making a living. In fact, many businesses prospered.

Businessman John McClelland opened a successful general store and ran the post office and apparently got along with all of his neighbours regardless of religious affiliation.

His large home featured an upstairs dance hall and meeting room and also doubled as a hotel. It is the only standing building left of the town and is easily identified by its large, frontier-style facade.

Mr. McClelland’s son eventually took over the store and over the next 100 years it was bought and sold many times.

When the railways of the 19th century started connecting the nation in a way that was never before possible, the decision was made to run the line being built between Hamilton and Allandale (Barrie), south past Ballycroy to Palgrave.

That decision forced many businesses to leave Ballycroy to take advantage of the opportunities the opening of the railway offered.

From there, the town slowly disappeared. The Orange Lodge was finally declared dormant in 1943, and the post office closed in 1951.

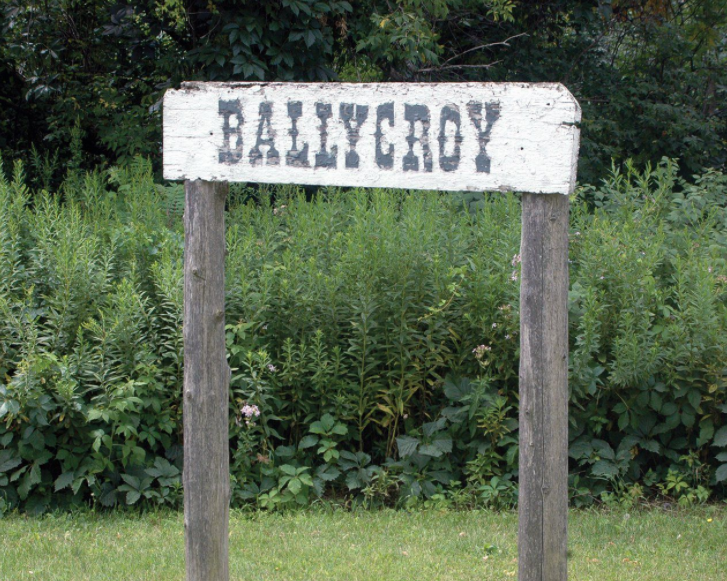

All that is left of the main street is an overgrown path that slopes gently down through a wooded area and a single sign with the town’s name that lets visitors know that this place once existed.

Brian Lockhart, Local Journalism Initiative, New Tecumseth Times