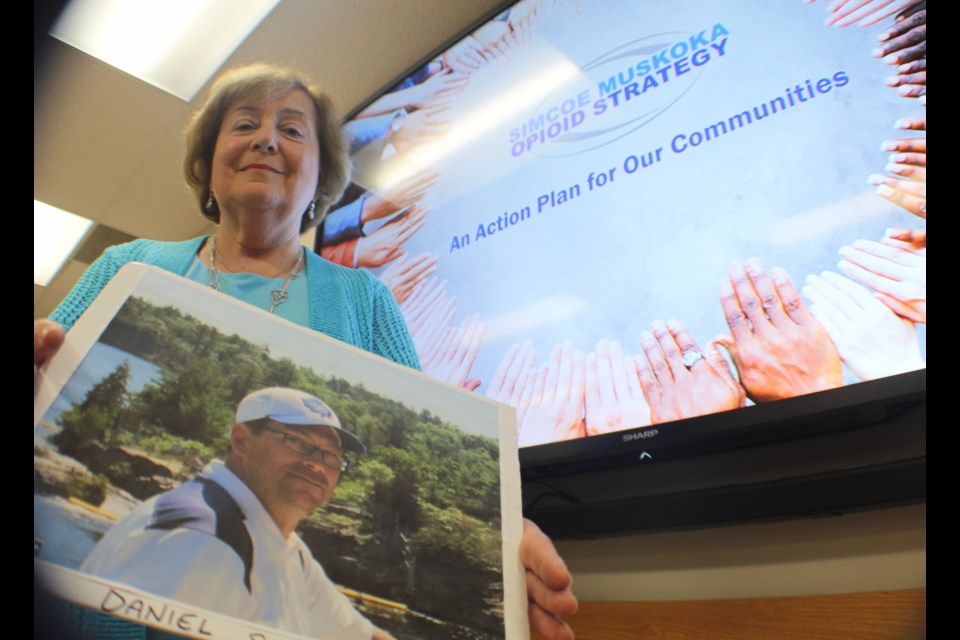

Beyond the mountain of statistics and numbers, the opioid crisis has a human element, people like Evelyn Pollack who have faced addiction and death head-on.

The Oro-Medonte Township woman lost her 43-year-old son, Daniel, to a Fentanyl overdose on Sept. 15, 2017.

“He had a lengthy life of difficulties,” she said. “He died from the use of Fentanyl, not knowing that it was Fentanyl.

“It took us four months to get the results from the coroner’s report and we had lost our son forever,” Pollock added.

Pollack was on hand Wednesday, along with her husband Dave, as the Simcoe Muskoka Opioid Strategy (SMOS) was unveiled at the Simcoe Muskoka District Health Unit building in Barrie.

“Our son died instantly,” said the Horseshoe Valley resident. “His brain stopped his body from breathing the night he injected whatever it is he felt he was taking.”

Pollock said Daniel’s death, with a needle that was still three-quarters full, illustrates how the smallest amount of Fentanyl can be deadly.

Formed in May 2017, SMOS is a regional partnership and collaborative effort to address the opioid issue in the area. Its ‘action pillars’ include prevention, treatment/clinical practice, harm reduction, enforcement and emergency management. The ‘foundational pillars’ on which SMOS is based are lived experience, data and evaluation.

When it comes to opioid deaths, the hardest-hit areas in Simcoe County are Barrie, Orillia and Midland.

“It was clear that we needed to do more,” said the health unit’s Dr. Lisa Simon, one of the co-chairs of the SMOS steering committee. “We needed to come together and address this issue more comprehensively and systemically. … (We needed) to have a conversation about opioids and how we can work together in a comprehensive and collaborative way.”

That includes everything from police to corrections and mental-health and health-care professionals.

In 2013 and 2014, there were 23 deaths in Barrie, 11 in Orillia and less than five in Midland. In 2015 and 2016, those numbers nearly doubled for Barrie (44) and Midland (9), while Orillia fell to nine.

“We have been above the provincial average since 2004,” said Simon, adding there was a “slow worsening” of the opioid problem in Simcoe Muskoka and Ontario throughout the 2000s.

“But it’s really in 2015, ‘16 and a dramatic spike in 2017 when we’ve seen this grow exponentially,” she said of the 70% jump. “It’s really the 2017 data over 2016 where we saw that dramatic increase.”

However, Simon said there is some positive news around the problem, which has shown some signs of lessening based on recent data. But whether it can be sustained or whether it’s a blip on the radar remains to be seen.

“Our numbers in 2018 to-date compared to 2017 to-date for emergency-department visits show that there may be a slight decline,” Simon said. “In Simcoe Muskoka and Ontario as a whole, it’s early to make any definitive comment, but it’s promising that there may be a slowing if not a very slow reversal to that trend.”

It’s too soon to tell why that could be, however.

“Like many other parts of Ontario, we are implementing the kinds of actions we’ve shown today,” said Simon, adding it’s not likely one specific aspect factor. “My best guess would be it’s a combination of all the factors and all of the resources that are being put in place to address this crisis.”

One area that is being addressed is the link between emergency rooms and paramedics, which help identify an opioid crisis in real time.

“Up until recently, our region has not had a co-ordinated, opioid-specific emergency management approach, so that’s a gap that we’re trying to fill,” Simon said.

In the 1990s, pharmaceutical companies in the United States began heralding opioids as a ‘safe and effective’ way to manage chronic pain, without much research to substantiate the claim.

That led to a “generational shift,” Simon said, in how opioids were prescribed. However, the lack of addiction services caused a “toxic situation.”

On the streets, people may be taking Fentanyl knowingly or not.

Pollock believes that’s what happened to her son, Daniel, who had battled addiction for many years.

“The problem is really an epidemic,” she said. “I believe we have to separate addiction from the opioid crisis. The opioid crisis is not about addicts and it’s not about addiction.

“Every family can experience this kind of loss. No one is exempt,” Pollock added. “And that is because synthetic opioids are coming into our country.”

Det.-Insp. Jim Walker, a member of the OPP’s Organized Crime Enforcement Bureau and who is heading up the law-enforcement pillar for SMOS, said police are working to identify the supply line thorough intelligence gathering and sharing.

“That includes meeting with our partners from the Canadian Border Services Agency, where we have intelligence that of the synthetic Fentanyl and Carfentanil derivatives are coming in from overseas,” Walker said. “Our is to target where it’s coming from and who’s responsible, either for the manufacturing or distributing.

“We’re making significant arrests,” he added. “Through intelligence-sharing, we’re getting a clearer picture.

“Every little community has its own supply-and-demand problems,” Walker said. “More importantly, though, and why we’re here today, is because we’re engaging with these other pillars. It’s a holistic approach and it’s not just a law-enforcement problem.”

Pollock said her son left the world with some “gifts” by chronicling his life story and experiences through audio recordings, which she then turned into a book, entitled ‘Thirty-Three Years to Conception’.

“It’s completely truthful,” Pollock said of the book. “And I love him because of what he saw, what he lived through and what his friends told us.”

The Pollocks adopted Daniel when he was five days old.

“We loved our son dearly,” she said. “He was a wonderful boy.”

Daniel began experimenting with marijuana around 14 years old, which led to alcohol, an addiction he had beaten for a decade. But he was never able to kick drugs. He had gone to rehab many times, but became homeless in Toronto where he would was often ticketed for panhandling.

“At the age of 33, he decided to come off the street,” Pollock said. “He came off the street and became a very big part of our life.”

Daniel soon began the recovery phase using methadone.

“Methadone is not a cure, it is another drug,” said Pollock, adding it did reduce his cravings.

The opioid crisis is affecting thousands of people, as the ripple effect from one death haunts a myriad of friends and family.

“Some of those families are silenced and they can’t speak out,” Pollock said, adding she has been contacted by many parents who are in a similar situation. “We can speak out, we have nothing to lose.

“None of us are safe until we get on top of this.”

For more information on SMOS, visit www.preventOD.ca.