This week's 'Remember This?' is Part 2 of a three-part series. To read part one, please click here.

Murders were, and still are, a rarity in the Town of Orillia, so the shocking events of March 1945 set the whole town abuzz and sent the police from local, provincial and outside forces into overdrive.

The investigators believed that the unfortunate Mr. Walker, night watchman at Vilas Enamel, had been attacked with two different weapons. He had been beaten about the head and face with what appeared to be a flat and blunt object, perhaps a metal strip connected to items manufactured nearby.

Walker had also been stabbed over 30 times with a knife or some other sharp object.

Early tips hinted that those weapons had been thrown into Lake Couchiching, which prompted a large-scale dragging of the entire lake bottom along the Orillia waterfront. After two days, the search had been fruitless and so was abandoned.

A systematic search of the Vilas plant also failed to turned up any weapons.

Teenage suspect Lloyd Simcoe was arrested without incident at his parents’ Front Street home, which was also thoroughly scoured for evidence. The police collected all of the clothing Lloyd had been wearing on that Saturday night.

At the point of his arrest, the police still had not found any clear motive as to why Lloyd Simcoe might have killed Freeman Walker. Robbery was discounted early on. Money and cigarettes were untouched in the company canteen. Only Walker’s key ring was missing.

So why was Lloyd Simcoe suspected so quickly? Without any murder weapons or motives, yet being under extreme pressure to apprehend some kind of madman on the loose, the police turned to the streets.

The Orillia News-Letter of March 21, 1945, reported that “several other youths around town have been brought into the police station for questioning. The results of these questionings have not been disclosed but it is believed that important information was obtained.”

Enter Lloyd Wellington Simcoe, described as slow and dull by his own family, who may very well have been the Guy Paul Morin of his time, that “weird-type guy” who didn’t quite fit in.

“18 Year Old Indian Held On Murder Charge” the headline read.

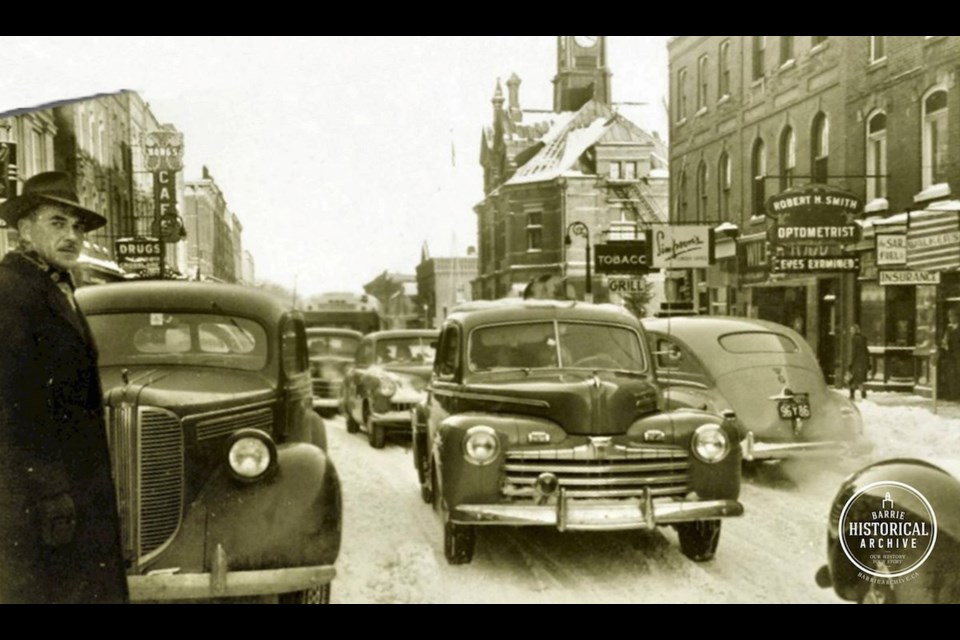

As Lloyd was being arrested at home, his younger brother, 16-year-old Elmer Simcoe, was picked up elsewhere in town and held on a vagrancy charge. Both boys spent the night in a local lockup and were transferred to the Barrie Jail at noon the next day.

Police Chief William Carson of Orillia freely admitted that Elmer’s vagrancy charge was nominal. The younger Simcoe was being considered a material witness and would be held for a short time, or a long time, depending on how long it took for the police to get what they needed from him.

Elmer Simcoe was released on March 23. Lloyd was transported to the Orillia police court for a preliminary hearing on April 6. On hearing day, a long line of citizens had queued up to attend the proceedings and, when the doors finally opened, a mad crush of spectators filled the courtroom to overflowing. Those without seats were removed and had to be satisfied with peering through windows from outside.

Mr. Frank Hammond acted for the Crown and Wallace Card had been hired by the Simcoe family to act as Lloyd’s defense counsel.

In these early years, police forces didn’t have the luxury of formal interview rooms, video cameras or audio recording capabilities. They interviewed their suspects in whatever space was available to them and used a variety of methods to pry the nearest thing to the truth out of the alleged offender.

The testimony at the preliminary hearing, as reported in the Orillia newspapers, gives me pause. Two police officers stated that they had placed Elmer and Lloyd Simcoe in separate holding cells a distance away from their office and then listened to see if they would say anything incriminating.

Apparently, it didn’t take long. In words sounding like they were ripped from the script of a bad film noir, Lloyd was reportedly heard to say to Elmer, “Well, I killed the old bugger and it serves him right.”

Neatly explaining the desperately sought motive, Lloyd also added, “And I can’t feel sorry after what he said to me,” a reference to racial insults Lloyd may have heard from Walker.

Mr. Card, Lloyd’s attorney, was most concerned about what Lloyd had said and when he said it. It seems that Lloyd, after being cautioned by the police chief, spoke briefly to Carson who then went back out to continue investigating the crime, leaving Lloyd with the officers at the station.

Upon his return, Chief Carson spoke to Lloyd again. Lloyd then wanted to backtrack on what he had said before and give a different story.

My question is why was a teenage suspect held and questioned with no counsel or parents present? These were different times, of course, but perhaps some readers with legal experience can enlighten me.

Lloyd was given an October trial date and sent back to the Barrie Jail to wait.

The murder trial opened at the Barrie Court House on Oct. 16, 1945. Again, there was a large audience including several school groups who attended every single day except the on the day of the sentencing, when they were excluded by the judge.

The defence counsel had his work cut out for him. His client had allegedly made several damning and contradictory statements while in police custody. Placing doubt upon the word of the highly respected local law enforcement would certainly be an uphill, if not impossible, battle.

Then there was the physical evidence. Remember, this was the pre-DNA era, although blood could be sorted into human versus non-human types by testing developed earlier in the 20th century. Eleven stains were found on the boots, shirt and coat belonging to Lloyd Simcoe and all of them tested positive for the presence of human blood.

Whose blood? How old were the stains? Nothing was found on the trousers that Simcoe had worn on March 17/18, 1945. How would a killer, who had committed such a frenzied and bloody crime, avoid being completely covered in blood himself?

Each week, the Barrie Historical Archive provides BarrieToday readers with a glimpse of the city’s past. This unique column features photos and stories from years gone by and is sure to appeal to the historian in each of us.