Four months. They only lived in Barrie for four months. But in that time, the Guthrie family left two ruined buildings in their wake, which led to a high-profile court case, and much investigating done by firemen, police, lawyers and insurance agents. Then they were gone.

What was later described as “the greatest sensation this town has seen for years” began the evening of Nov. 17 in 1909. Around 10 p.m., the fire alarm was sent out that a house on Thompson Street in Barrie was on fire. The residents, the Guthrie family, had gone out for the evening. The fire was spotted by neighbours and the fire brigade was there quickly and in full strength.

Things began to take a strange turn when the firemen gained entry into the house. The smell of coal oil was immediately apparent. The first two wooden steps of the main staircase had been burned right through, but little else nearby had been badly damaged. However, the side door to the kitchen, many feet away, was also burned. On the second floor, matches were strewn about, and an oddly placed peach basket was sitting on the floor. Partly burned, it contained rags that smelled strongly of kerosene.

While the firemen were puzzling over the situation at the Thompson Street house, they received a request to attend another fire. This confused them at first as quiet little Barrie had never had two fires simultaneously. It took a bit of convincing to assure them that this was actually the case. The bulk of the men went off to the new fire while a couple of brigade members stayed on the Thompson Street site.

Bruce Thompson, a man who rented a flat above the then Beecroft Bank at Dunlop Street East and now Fred Grant Street, spotted smoke sneaking out of the windows of the King’s Music Hall next door and gave the alarm. Thompson took a walk around the building and saw a telltale orange glow through a glass door. He broke the door and found that there was no fire on the first floor but that flames from the upper floor had begun to burn through the ceiling.

The music hall, which I have only recently discovered, was part of the early life of the currently being renovated Bank of Montreal building on Fred Grant Street. Built in 1891, it had soaring arched windows that reached from the second to the third floor. Third floor – what third floor? This fire of 1909 likely led to its removal.

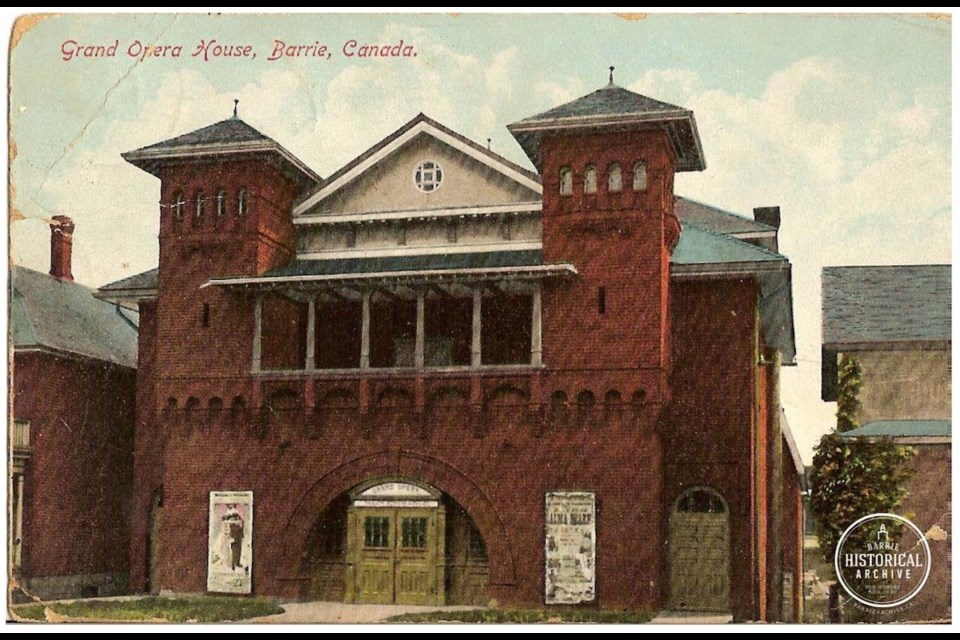

From 1891, until about 1896, the music hall did a great business showcasing all the singers, quartets, bands and theatricals of the day. The opening of the Grand Opera House on Collier Street would have changed the entertainment business in Barrie. By the early 1900s, the Kings were looking for new opportunities to keep their hall going.

So, in November of 1909, the hall was home to the Crystal Moving Picture Show, where early silent films were shown. The picture show operators, who leased the space, were fairly new in town. Mr. and Mrs. Samuel J. Guthrie only arrived in Barrie from Peterborough that past August.

Yes, it’s true. How unfortunate can any family be? To leave home to attend to your business, and have your house go on fire, only to rush to that emergency and learn that the place of business you just left had also suffered a fire, must be a tragic coincidence of the worst kind.

Mrs. Guthrie especially must have been terribly stressed. After all, she had already had a very busy day. She had been trying to purchase contents insurance for her rented home and also for the moving picture equipment at the music hall for some time, and only had that day finally secured some fire insurance.

The entire situation was so very obviously suspicious in nature that Mayor James Vair called for an inquest. Led by Coroner Wells, it began two days later in the Court House. The local interest was so great that proceedings had to be moved from the usual Police Court room to the much larger High Court room, and that too was packed.

Samuel Guthrie, who still had some business dealings in Peterborough, had been away during the whole ordeal. Mrs. Guthrie and some of children were the persons of interest that the court wished to question. Two picture show employees, firemen and some baggage handlers at the Allandale Railway Station were also called to testify.

The Coroner’s jury had been given a tour of the Guthrie home and were rather startled by what they saw. The multiple fire sites throughout the home were strange enough, but picture frames hanging devoid of family photographs, and beds without quilts, gave the impression that someone had had a premonition about the events to come and had removed any precious items beforehand.

During the investigation, there was mention made about a mysterious boarder, a Miss Lillian Meeks, who had been living with the Guthries for a couple of weeks before the fire. Where did she come from and where did she go? No one seemed to know and Mrs. Guthrie became quite a hostile witness after being pressed repeatedly about Miss Meeks.

Miss Meeks became a central figure to the case when it was learned that she moved out of the Guthrie home just hours before the fire. All of her belongings were contained in two large steamer trunks and had been removed by J.C. Hirons, a livery man from Allandale, at the request of Mrs. Guthrie. She didn’t give her address on Thompson Street but instead told Hirons to meet a boy at nearby Brown’s Bakery for further instructions. Hirons later testified that the boy, who identified himself as a son of Charles Jones a local painter, was actually one of the Guthrie boys.

And what of these trunks? They were brought to the Allandale Railway Station where Mrs. Guthrie, accompanied by Lillian Meeks, paid for them to be shipped to Elmvale for storage. The baggage handlers identified the Guthrie’s 18-year-old daughter, Clara, as being one and the same with Lillian Meeks.

The trunks were confiscated and brought to the court where they were opened. Inside, were Guthrie family photographs, heirloom quilts, scrap books and even the family Bible. Mrs. Guthrie tried to suggest that Miss Meeks must have stolen these things. No one was too receptive to that idea.

Both Mrs. Guthrie and her daughter, Clara, were charged with arson and perjury. A bondsman, James Goodwin, posted their bail. On Dec. 1, he revoked the bond on Clara because her mother had disappeared. Tales from passengers aboard a Barrie to North Bay train about a woman disguised as a man on board, quickly became a possible explanation as to how her departure was accomplished.

Miss Clara was lodged in the Barrie Jail for the better part of a month after that. Thanks, Mom!

The young lady was given likely the best Christmas present of her life when her case was thrown out due to a technicality on Dec. 23.

Clara was next heard from in a wedding announcement upon her marriage to Andrew Zac Snider in 1914, in Sharbot Lake, Frontenac County, Ont., where she was born. Interestingly enough, her birth registration says she was born 160 km away in Harvey Township, outside Peterborough.

Mrs. Guthrie, the former Theresa Traynor, who was reportedly born in Washington State, U.S.A., of all places, was mentioned in a Northern Advance from July 11, 1912. It reported that Mrs. Guthrie, of the music hall fire fame, had been badly injured in a tornado that had killed one of her other daughters, Etta. They were living in Regina, Sask.