We were the last family to live there. The simple white-siding bungalow was built in 1960 and is still livable today, but no one wants to raise a family there. Other than seasonal farm workers at times, the house has largely stood empty since 1985.

The problem is the location. My childhood home sits in one of the most isolated spots in Simcoe County, down a dead-end road, in the middle of a very wet and mosquito-infested swamp. The railway crossing, on the dirt road to it, only recently received lights when the GO Train began running.

Surrounded on three sides by thick bush, and Cook’s Bay where it meets the Holland River on the other, we were miles from everything. The winters were particularly isolating with the constant silence only broken by the sounds of train whistles, snowmobiles or passing planes.

Why, oh why, would anyone want to live at the bottom end of the 13th Line of West Gwillimbury Township? Ever.

It is a valid question, and apparently today, no one does.

The first time I ever laid eyes on the house was in 1968. We were given a tour of the house by my father’s new employer, William ‘Bill’ Watson Jr., a Scottish immigrant like my father. In the basement, the wooden rafters were covered with the most unbelievably large collection of muskrat pelts. Bill saw the look of horror on my little face and assured us that those furs would be gone when we moved in. They were.

Those pelts were actually the key to why this land was developed. Bill was the son of a Holland Marsh farmer who had operated on the main marsh south of Bradford since the 1930s. Muskrat hunting with his brother-in-law brought Bill down to this lonely swamp in the 1950s, and he saw there potential for a market garden business.

He cleared and drained the land, and built a road to it when the township ran out of money to finish it. Bill then had a three-bedroom house built for himself and a round-roofed Dutch style barn.

Bill Watson himself never lived in the house, as far as I know. He was never in the best of health and his wife was accustomed to town living, so he stayed in Bradford. He worked the farm and hired a farm manager to live in the house and look after the daily farm tasks. That is how we came to be there.

Surprisingly, Bill Watson was far from the first person to take an interest in this location and live within this part time bayou.

The farm has two types of soil. The land closest to the river is what is known as muck soil; black earth once the bottom of an ancient lake, as makes up most of the Holland Marsh. Farther west, as you approach the ridge near the railway tracks, the land is sandier mineral soil. Each type of soil has its particular uses.

The highland fields, the ones containing mineral soil, sometimes yielded evidence of long-ago aboriginal encampments. My father still has a shiny black stone ax head that he found there years ago. Visiting anthropologists once confirmed to him that this place had been a stop for the indigenous people on their seasonal migrations.

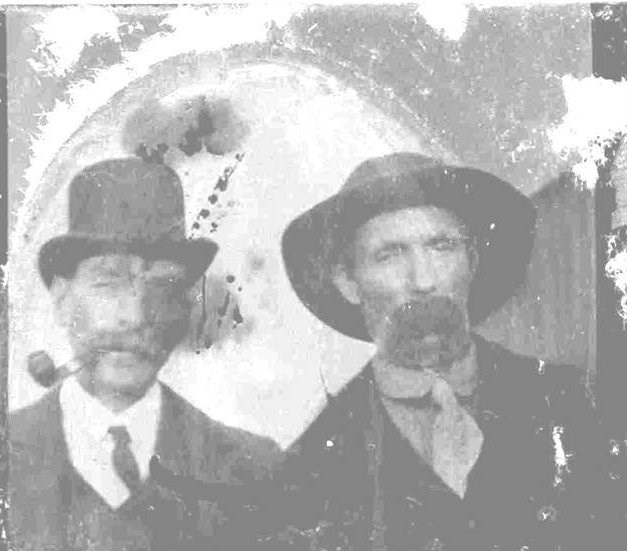

But likely the most fascinating of all the hardy folk that ever called this forgotten place home was Henry ‘Sank’ Lowe.

Sank Lowe was the son of an English-born butcher, Robert Lowe, and his wife Isabella. The census of 1891 finds 18-year-old Sank still at home with his parents, single, and occupied as a trapper. It would seem that the abundant muskrat population may have lured another adventurer down the 13th Line.

I don’t know what kind of a fellow Sank really was, but I suspect he was a unique man, maybe a bit of an eccentric, not someone all that willing to conform to all of the rules that society dictated. Although he married in 1893, his wife Elizabeth does not seem to figure into any of the later narratives of his life. The 1911 census lists him as married but his only housemates are a female housekeeper and a male servant.

But we were unaware of all of these things when my siblings and I ventured into the woods in the summer months of the 1970s. With no water bottles in those days, we stopped at a clear running stream to take in some cool water and wondered at the strangely out of place junk pile a mile from the nearest road. My father explained to us that the older neighbours in the area remembered a man who used to make whisky back in the bush – the notorious moonshiner, Sank Lowe!

Dad had often come across evidence of Sank’s time on the 13th when plowing the highland fields in the same area the former aboriginal camp. He regularly disturbed bits of smashed china dinnerware in one particular section of the land. This spot, next to the winding stream, appropriately named Sank’s Creek, was where the moonshiner made his home.

Yes, he farmed, at least he did in the beginning and maybe just part-time later on. In those years, in the 1920s, the concession road did not reach Sank’s property, but an old wagon road ran diagonally from the river’s edge, past his cabin, and into the forest, then through to the 14th Line and perhaps even as far as Gilford. Marsh hay was cut for mattress stuffing and carted to waiting train cars northwest of the farm. The spot where the wagon road entered the bush is still visible 90 years later.

Whether by financial necessity or otherwise, Sank Lowe set up a still in the woods over a mile from his home during the Ontario Prohibition years and become possibly the best known of the many swamp whisky men in Simcoe County. In the 1970s, my family attended a reunion in eastern Ontario and met a former Toronto resident who well remembered taking detours down the 13th Line. On the way home from his cottage, during the 1920s, he often stopped there to buy a box of liquor to sell down in the city.

When an illegal business does so well that it is known far and wide, it won’t be long before the law hears of that success as well. The archives of the ‘Barrie Examiner’ and the ‘Northern Advance’ newspapers are full of reports of Sank’s numerous arrests and appearances before a Barrie judge. At one point, the judge just shook his head and remarked that this whisky-making venture that Sank was running must be some kind of obsession as he couldn’t see that Sank had ever made any real money at it.

Sank made the papers once though, for a very different reason. One tremendous summer thunderstorm created a great gully below the railway tracks near his cabin and Sank Lowe flagged down the train before it could reach the washout and surely derail. For his efforts, he was awarded a medal and reportedly given free train passage for life.

However, after numerous visits to the Barrie court house, Sank was sent up to prison for just short of two years. The local story is that a horse or mule got into Sank’s cabin, during his absence, got locked inside, kicked the interior to pieces and died in there. After this, Sank was never associated with the place again, but pieces of destroyed household contents keep rising to the surface every year.

In late April, some of my family members including my 86-year-old father, myself and an interested neighbouring farmer, took a hike down to the bottom of the 13th Line to see if we could find any remnants of old Sank and his life in the swamp. The location of the still, if anything remains, was too wet to access but we may return another day. With my father’s still sharp memory guiding us, we wandered around the soon-to-be-planted highland field and sure enough, found a handful of broken bluish china, white fine china, bits of glass, and rock that may have come from a foundation. One sharp stone might be an ancient arrow head.

The Watsons gave up the farm over thirty years ago. Some very fine farmers of the Srebot family have expanded the marsh operation and keep the property looking neat and well-tended. The highland fields are rented out to John Hambly of Gwillimdale Farms, another fine businessman.

Great for farming, muskrat hunting and moonshining, the land at the eastern end of that quiet concession road is just a little to out-of-the-way for most 21st century families to consider. Sank Lowe loved it. My family, who came from even more isolated places in the west highlands of Scotland, enjoyed the lonely spot for nearly twenty years.